Copyright © Eddie Tricker

Size

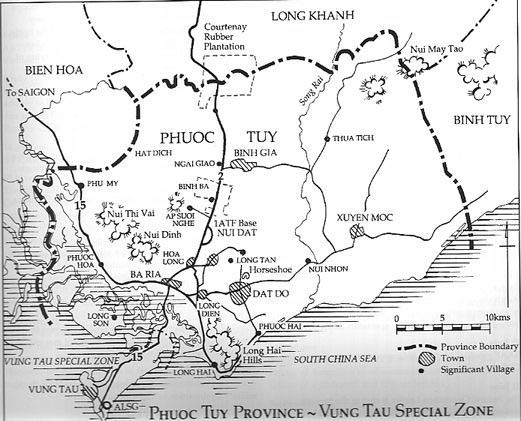

Phuoc Tuy Province, which is about 50 kilometres from north to south and 40 kilometres from east to west, has an area of 1958 square kilometres, which is approximately the same size as the Australian Capital Territory. Phuoc Le, (also known as Ba Ria or Baria) the Provincial Capital is about 110 kilometres by road from Saigon. At the time of the Australian involvement in South Vietnam, Phuoc Tuy had a population of approximately 106, 000 people in villages and hamlets grouped along and around the major road ways within the provinces, namely Routes 2, 15, 23 and 44 to the south of the province.Agricultural Economy

The economy of the province was primarily agricultural, with rice the staple crop. Phuoc Tuy was considered part of the "Rice bowl" of Vietnam. Many other tropical crops such as rubber, banana, peanuts, coffee, tobacco and pepper were also grown, whilst local fruit such as Longan, Rambutan and Lychee freshly picked that very morning, filled the local markets of the larger villages.Coastal villages concentrated on fishing activities and production of Nuoc Nam, the Vietnamese fermented fish sauce. There were daily herds of cattle and groups of water buffalo that moved along the roadside to till the fields.

Wooden wheeled Buffalo carts, used by wood croppers, constructed to a timeless design handed down from generation to generation were common place on the local roads. Italian Lambros (Lambretta 550 cc scooters fitted with micro-bus cabin bodies) had an amazing ability to carry any and everything, together with some old fashioned cars and buses with the ever present two stroke motor cycle provided the means of transport in the province and across the country.

Topography

The topography of the province was essentially that of a flat country side with three isolated mountain or hill groups; the Long Hai's in a south easterly direction and located approximately sixteen kilometres from Nui Dat; the Nui Dinhs and Nui Thi Vi's in a south, south westerly direction and located approximately seven kilometres from Nui Dat and the Mao Tao's in a north, north easterly direction and located approximately thirty kilometres from Nui Dat. The Long Hai and Mao Tao mountain groups had strong reputations of being (and were) strongholds for the Viet Cong whilst the Nui Dinh and Nui Thi Vi group had a similar reputation, but to a lesser degree.Historically the Long Hai mountain group had always been a base stronghold for guerrilla and resistance groups and were well provided with caves carved out over history by these guerrilla groups. The French never did contain the enemy forces that lived in these mountains.

Climate

The climate was very predictable; the dry season from November to April and the wet season, with overpoweringly high humidity and rain from May to October. Year around temperatures of 27o Celsius (80o F) except January and February which were quite cold with temperatures that averaged about 16o C (60oF) were the norm. The dry season is very similar to a cold Australian autumn without any rain. The leaves fall off the rubber trees, there is no rain so that the dust starts to fly and it is very cold at night time especially on top of any of the mountain or hill groups.Currency

South Vietnam's unit of currency was the piastre or dong. Notes were issued in denominations of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 and 1,000 piastre or dong, whilst coins were minted up to 20 dong or piastre.Service personnel were entitled to a special exchange rate which at the time represented a 47% mark up on the normal market prices, so that:

118 piastres or dong to 1 American dollar

131 piastres or dong to 1 Australian dollar

221 piastres or dong to one pound sterling.

131 piastres or dong to 1 Australian dollar

221 piastres or dong to one pound sterling.

There was also a "black market" in currency, however dealings in the "market" were strictly forbidden to Australian troops.

Australian troops were issued with American "Military Payment Certificates", known as "MPC", as soon as they landed at Tan Son Nhut Airport, Saigon. This was part of the formal process of the "welcome to South Vietnam" where Australian currency held by the incoming troops was converted at an Army exchange office at the airport. One cent "MPC" was equivalent to one American cent.

MPC were, "For use only in United States military establishments - By United States authorized personnel in accordance with applicable rules and regulations." They were issued in denominations of 5, 10, 25, 50 cents, 1 dollar, 5 dollar and 10 dollar, etc in series runs. From time to time these series were withdrawn from circulation without warning and replaced with a new series with a completely new design and look.

This way the American "system" fought against the currency "black market". Troops were told that a pay parade had been called, they fronted up to the pay office and simply exchanged equivalent old MPC for the new issue.

Prices at Australian Bases in South Vietnam were very cheap in 1970. A can of "Victoria Bitter" beer could be purchased for 10 to 15 cents MPC, whilst a carton of Bensen & Hedgers cigarettes cost only $1.40 MPC.

Time

Vietnam is eight hours ahead of Greenwich mean time and is therefore three hours behind Sydney, (Australia) time, or 4 hours during daylight saving. That is when it is 3.00pm in Saigon, it is 4.00pm in Sydney, Australia (Eastern Standard Time).Religious Structure

The religious structure of South Vietnam is very complex with a great many religions having made an impact upon the culture and population of the country. In Phuoc Tuy, the religion of the population in the main was Buddhism although there are a significant proportion of Catholics with remnants of the population representing the other major and new religions such as Confucianism, Taoism, Cao Dai and Hoa Hao.Education System

There was an adequate primary schooling system and the opportunity for some to proceed to secondary schooling. The village and village school was the centre of most people's lives.Security

The view that the local inhabitants of the province had of the region's security situation is very difficult to understand. The province was clearly in an armed state just short of war. Each village and vital point, such major river bridges, had protective military posts, usually occupied by soldiers, their families and assorted pigs and poultry. All men of military age were liable to be called up for military service in the Army of the Republican of Vietnam, Regional Force (RF), Popular Force (PF), or the Peoples' Self Defence Force (PSDF). The South Vietnamese Government controlled the province by day. But it was clear that the Viet Cong ruled the province by night. The state of war drew artificial lines of access on maps around villages; there were allied defined civilian access zones which were relatively safe havens and to which strict curfews were applied and defined free fire zones in the countryside where almost any movement by any Vietnamese national was defined as Viet Cong movement.But the Viet Cong clearly ruled the darkness of night, kidnapping and assassinating village officials, imposing taxes by the collection of basic food stuffs such as rice and dried fish, press ganging of village young people into their ranks almost at will.

It is extremely complicated to describe Phuoc Tuy province, people and sights. Most of country people chose to ignore the presence of Australian soldiers. The rice farmers would become wood cutters during the dry season.

The young school children neatly dressed in their schools uniforms whilst the elder slender girls of teenage years and older dressed in their black silken trousers with white silken Ao Dai's ( pronounced "Aow Zai") moving in groups to and from the village school, twittering with shyness at the closeness of Aussies moving amongst their midst.

The street urchins that grinned and shouted "Uc Dai Loi number one, you give me cigarette", as they begged for all and everything that a good hearted Australian digger might give them. The village kids that rode on the backs of their cattle and water buffalo as they moved them at the crack of dawn along side of the major roads grazing them whilst they moved along.

To the ancient, unattended rubber trees that we placed our tent lines under to gain some relief from that hot tropical sun and the white latex sap they bleed when one used them for bayonet throwing target practice. To that unforgiving red, bright rusty red volcanic laterite clay soil that clung to the soles of our boots during the wet season and during the dry season caused conjunctivitis, fine red dust invading and covering everything it touched. This contrast between the wet and dry seasons, the jungle and the rice paddy fields were all those things that made a lasting impression on the minds of all those young soldiers who served in South Vietnam.

Add to this the strange jungle smells of rotting vegetation; the eerie glow at night of the phosphorescence of decaying ground leaves that had been disturbed to clear a sound-free path simultaneously with the multiple flashes of fireflies as they tried to out shine one another, and the haunting bark of jungle geckoes that caused many a young soldier to experience apparitions in the jungle night. Such were the contrasting experiences of many of the young infantry soldiers that fought the Viet Cong soldier.